What if I told you that your chronic back pain might actually be caused by tight fascia in your feet? Or that the stiffness you feel getting out of bed could be resolved by working on your glutes and hamstrings instead of your spine?

You might be surprised to learn that the nagging ache between your shoulder blades after computer work, the stiffness that makes you hobble for the first few steps each morning, or the mysterious tension that wasn’t quite muscle and not quite joint might come from a completely different part of your body than where you actually feel it.

Most of us don’t realize that the web of connective tissue beneath our skin—our fascia—can be the root cause of those everyday aches, tightness, and especially chronic back pain. Research published in Frontiers in Physiology shows that fascia plays a central role in pain perception and mobility, yet it remains one of the most overlooked factors in chronic stiffness and low back pain.

Let’s dig into what fascia is, why it tightens, and how simple self-myofascial release techniques can help you move better, feel better, and age with greater ease.

The Hidden Web that Controls Your Movement

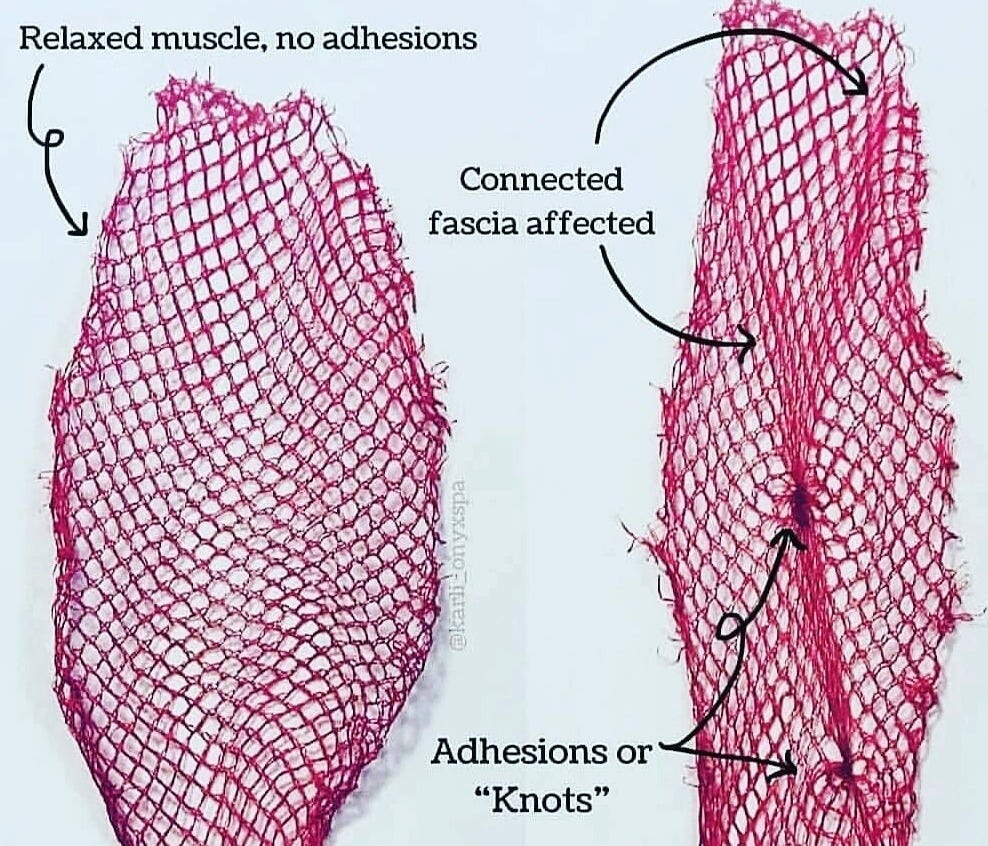

Think of your body like a sweater—pull one thread and you’ll see puckering somewhere else. That’s similar to how fascia works.

Fascia acts as your body’s scaffolding. It’s a thin, fibrous network that wraps around muscles, bones, nerves, and organs. It holds everything together and keeps things gliding smoothly. When fascia becomes stiff, sticky, or dehydrated, it pulls on other tissues and creates imbalances that can show up as pain or restriction that often manifests in the low back, hips, and hamstrings.

Fascia is responsive to both physical and emotional stress. Emotional stress can cause fascia to tighten reflexively, just like a muscle contracting in anticipation of danger. Over time, this contributes to a constant, low-grade tension in areas like the neck, shoulders, and back.

Why You Feel It in Your Back

The low back is one of the most common areas of pain and tightness. Low back pain is the leading cause of disability worldwide, and in most cases, it’s considered non-specific or idiopathic, which means that the symptoms arise without an identifiable cause or underlying condition.

Women over 55 are especially prone to low back pain and stiffness, not solely due to aging, but also because of hormonal changes associated with menopause. The decline in estrogen during menopause is linked to increased stiffness and reduced flexibility in connective tissues, including fascia, which can contribute to greater tension in the low back, hips, and hamstrings.

Many people don’t realize that low back pain may not be coming from your low back at all. So if it isn’t coming from your low back, then where’s it coming from?

The answer to that question may be your fascia. Fascia connects your body in continuous lines—sometimes referred to as myofascial chains or fascial trains. These connections mean restrictions in one area can radiate tension or lead to compensatory movement patterns elsewhere. This concept is widely recognized both in clinical practice and anatomical research, and is particularly important to understanding pain and mobility issues, including those experienced by older adults.

For example:

Tight hamstrings can pull the pelvis into a posterior tilt, increasing strain on the lumbar spine.

Shortened hip flexors or quads—often from prolonged sitting—can pull the pelvis forward, also straining the low back.

Gluteal restrictions can reduce hip mobility, shifting the burden of movement to the lumbar region.

Stiffness in the thoracolumbar fascia—a dense web that connects the lower spine, glutes, and lats—can limit rotational and side-bending movements, leading to overcompensation elsewhere.

Tightness in the soles of your feet or calves can affect your gait and posture in ways that ripple upward to the spine.

This interconnected web means that when fascia gets sticky, dry, or overly tense, the low back is affected even if it’s not the source of the problem. By releasing fascia in adjacent or connected areas (like the quads, hips, hamstrings, or even mid-back), you can often alleviate tension and reduce pressure on the lower spine.

What's Making Your Fascia Fight Against You

Here’s what causes fascia to lose its flexibility and function:

Sedentary Lifestyle

When we don’t move enough, fascia can become stiff, dry, and less elastic. It loses its ability to glide smoothly over muscles and tissues, which can lead to tightness, reduced mobility, and discomfort.

Repetitive Movement Patterns

Doing the same motion over and over—like sitting, walking a certain way, or sleeping in one position—creates imbalances in tension that affect posture and joint function.

Injury or Surgery

Scar tissue and fascial adhesions develop as the body heals, sometimes pulling on nearby tissue in ways that cause pain elsewhere.

Chronic Stress

Emotional stress doesn’t just live in your mind. It shows up in your body. Like muscles, fascia can reflexively tighten in response to anxiety, fear, or chronic worry. Over time, this low-grade tension builds up in places like your neck, shoulders, and low back. Ongoing stress can keep fascia in a contracted state, leading to tension-related pain.

Dehydration and Fascial Drying

Think of fascia as a sponge. When we move, it’s like squeezing and releasing that sponge, drawing in fresh fluid. But when we’re sedentary, that sponge compresses and dries out.

When your fascia is chronically dehydrated from lack of fluid or lack of motion, the fascia stick together and create adhesions. And once that happens, no amount of water will get them unstuck. Movement and friction are the only way to break up the adhesions so that the fascia can once again absorb fluid.

Aging

As we age, fascia produces less collagen and hyaluronic acid—key elements that help it stay elastic and hydrated. Our natural movement variety also decreases.

But with the right care, fascia can regain flexibility and fluidity. A recent study found that fascial release with a foam roller combined with core stability exercises was safe and effective in reducing non-specific lower back pain in older adults.

The Simple Solution: Myofascial Release

Myofascial release is the practice of applying gentle, sustained pressure to tight or knotted fascia using tools like foam rollers and massage balls. This pressure loosens the adhesions, which allows the “fascial sponge” to hydrate, releases stuck areas, and helps restore normal movement patterns.

Your fascia and the collogen within it turn over approximately every 2 years. That means you have the ability to remodel your fascia and rid yourself of the associated tension and pain simply by using myofascial release techniques that you can do at home with minimal tools.

A 2024 randomized controlled trial published in Frontiers in Physiology found that foam rolling of the lower back significantly improved lumbar spine mobility and increased the pressure pain threshold in healthy adults. These benefits were observed after a single session and became even more pronounced after a 4-week program, with effects lasting up to 6 months.

The Power of Mindful Breathing

Your breath is a powerful partner in myofascial release. When you hit a tender spot while using a foam roller or massage ball, your instinct might be to tense up or hold your breath, but that can actually make the discomfort worse.

Instead, use your breath to help your body relax and release. Take slow, deep inhales and consciously soften into the pressure. This tells your nervous system it’s safe to let go, allowing the fascia to release more effectively. Try this breathing pattern: inhale for a count of 4, hold for 2, then exhale slowly for a count of 6. As you breathe out, imagine the tension melting away. With practice, this gentle focus helps your body ease tightness more naturally.

🎯 Reminder: If you’re 55+ and struggling with chronic tension, fascia might be the missing link you’ve been looking for.

How to Target the Right Areas for Back Relief

These are the most effective areas to target for low back relief and overall mobility:

Mid-Back (Thoracic Spine): Lie on a foam roller placed horizontally beneath your shoulder blades. Support your head, engage your core, and gently roll up and down.

Hamstrings: Sit on the floor, legs extended, foam roller under your hamstrings. Use your hands to lift your hips and gently roll.

Quads: Lie face down with the roller under your thighs. Roll from your hip hinge point to just above the knee.

IT Band (Side of Thigh): Roll the outer thigh gently with a soft roller or massage ball. Avoid digging deeply, which can irritate tissue. and stay above the knee. This is a sensitive area, so you may need to reduce the amount of pressure you use. Using the massage ball against a wall is an option if you experience significant discomfort using the foam roller.

Calves: Sit with legs straight, roller under your calves. Use your hands to lift and roll from ankle to knee.

Glutes: Sit on the foam roller with one ankle crossed over the opposite knee to target one side at a time. Lean slightly toward the side you're rolling and slowly move back and forth over the glute muscle for 30-60 seconds. Pause on any tight or tender spots and breathe deeply. Switch sides.

Massage Ball Techniques: Use a massage ball against the wall or floor to gently apply pressure to glutes, calves, quads, hamstrings, IT band, and upper back (between the spine and the shoulder blades). Move slowly in small circles or hold pressure on tight spots.

💡 Tip: You can use a tennis ball or rolling pin from your kitchen in place of specialized equipment.

What Equipment Should You Start With?

For Beginners: Start with a soft-density foam roller (36” for versatility 18” for portability and maneuverability) and a tennis ball or massage balls. This combination covers most areas effectively and gently.

Foam Roller Options:

Soft rollers (low density): More forgiving and better for beginners and sensitive areas.

Medium Firm rollers (medium density): Provide deeper pressure but may be too intense for some, especially if you’re just starting out.

Length: Full-length (36”) for larger areas; shorter (12-18”) for portability and floor space issues. Shorter rollers may also be easier to position when targeting certain areas such as the inner thigh and groin.

Massage Ball Options:

Tennis balls: Great for sensitive areas and beginners. Widely available.

Lacrosse balls: Firmer pressure for deeper release.

Rubber massage balls: Professional option with consistent pressure.

I use both tools regularly and find they complement each other well. The foam roller is my go-to for larger muscle groups. It’s excellent for releasing tension in my hamstrings, quads, or mid-back. But the massage ball is where the magic happens for pinpoint tension. When the foam roller can’t quite reach that specific knot in my glute or that tight spot along my IT band, the ball gets right to it.

What I love most about massage balls is the convenience. I often find myself rolling a ball on my quads or under my hamstrings while sitting at my desk, or sitting on it when hip tightness creeps in during long work sessions. When I need a quick release and don’t have the floor space, I just walk over to a wall and use it there. No setup, no getting down on the ground—just immediate relief wherever I am.

Start with what you have, and build from there based on your needs and comfort level.

Is It Safe for You?

New to Foam Rolling: If you’re new to foam rolling and worried about safety, start with gentle tools like a tennis ball or massage therapy ball and short sessions (1-2 minutes per area). It should feel like a deep tissue massage; not pain.

Osteoporosis: Proceed with caution. Avoid direct pressure on the spine or hips. Use soft-density rollers and focus on areas with muscle padding.

Fibromyalgia or Chronic Fatigue: Take a gentle approach. Use very soft tools, limit session time, and avoid painful areas.

Blood Thinners or Blood Pressure Issues: Check with your doctor first. Use light pressure and avoid bruising. Move slowly.

Joint Replacements: Avoid rolling near or directly over replaced joints. Focus on surrounding muscle groups. Check with your doctor or physical therapist (PT) first.

Can’t Get on the Floor: If you’ve been told not to get on the floor, try seated or standing techniques using a chair or wall, or use a firm bed or bench for modified rolling. Using massage balls instead of a foam roller may be a better option for you. Work with a PT or certified trainer for alternatives.

General Rule: If it’s painful, back off. Foam rolling may feel slightly uncomfortable, but if it feels like punishment, lighten up on the pressure. You should never feel sharp or intense pain when performing any exercise.

Check with Your Doctor: Before starting any new exercise or program, check with your doctor to make sure it’s safe for you.

The Science Supporting Myofascial Release

Fascia is no longer viewed as just packing material or structural filler. Emerging research shows:

According to a systematic literature review, fascia has its own nerve supply and is richly innervated, especially in the thoracolumbar region, explaining why fascial restrictions often present as deep, diffuse, or hard-to-localize discomfort.

Research continues to explore how stress—both physical and emotional—alters fascial tone through the autonomic nervous system

Self-myofascial release can improve range of motion, reduce delayed-onset muscle soreness, and alleviate pain

These findings underscore the importance of fascia-focused practices, especially as we age. With consistency, hydration, and mindful movement, fascia can regain its suppleness, thereby helping you move with greater ease and less pain.

Your Next Step

If you’ve been chasing pain without lasting relief, maybe it’s time to try a new approach. Instead of focusing only on where it hurts, start looking at how your body moves as a whole. You might be surprised to find that your nagging back tension eases when you begin working on the fascia in your hips, hamstrings, or even your feet.

That’s why I’m excited to share my upcoming 28-Day Mobility Reset. I’ve partnered with a trusted mobility expert to bring you high-quality, daily videos designed to help you move with more ease, reduce everyday stiffness, and feel better in your body. The program includes gentle, fascia-focused foam rolling you can do at home, even if you’re brand new to it.

More details are coming soon, and I can’t wait to invite you in.

Let’s keep the conversation going:

Where do you hold the most tension in your body? Is there a spot that always feels tight or achy? I’d love to hear what you notice and whether you’ve tried foam rolling. Share in the comments—your story could help someone else.

This post is packed with valuable information, Daria! Thank you!

It’s wild how tightness in places like the feet or hamstrings can ripple all the way to your spine. I love that this piece highlights the power of myofascial release and mindful breathing to gently unlock those tension knots.

This post is power-packed and absolutely essential for everyone. Mobility is everything as we age. Thank you Daria!